Revenue is easy, profit is harder

The fundamentals needed to run a business in the next economic cycle.

In 2010, when the market was recovering from the great financial crisis, capital was not easily available. During this time, I started two companies — a mobile gaming company and a performance-marketing company.

My bootstrapped mobile gaming company achieved success, reaching $3K+/day and at times being the number one or two mobile word game on the iPad. Despite the opportunity, I was hesitant to double down and jump in the game of venture capital.

So, I co-founded a performance-marketing company with a veteran from the previous technology cycle. We scaled multiple business lines from zero to millions of revenue as a bootstrapped company. During this process, I learned the importance of capital efficiency and how to run a profitable technology business.

Now, as a venture-backed founder, I have observed that few people understand these nuances and the significant role they play in running a business for the next economic cycle.

Profitable Growth

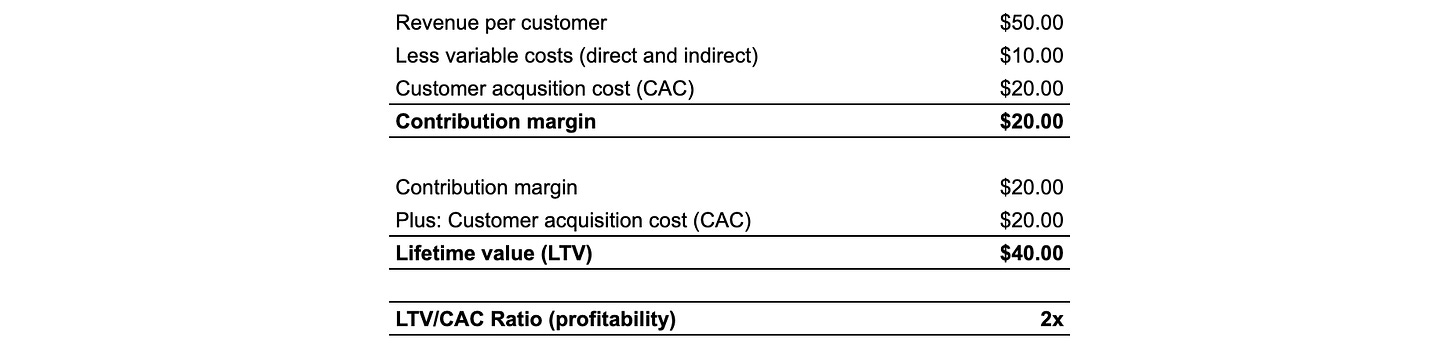

In simple terms, positive unit economics means that a company is making more revenue from a customer than the costs that are being incurred to acquire and service the customer.

If a company spends $20 to acquire a customer that generates $50 in revenue, and they have $10 in variable costs, then the contribution profit would be $20 (i.e. revenue less variable costs less customer acquisition costs). Adding back in the customer acquisition costs, the company would have a lifetime value (LTV) of $40 and an LTV/CAC ratio of 2.0. This means that they are able to make $2 for every $1 spent on acquiring a customer.

Generally, if they can generate $40 in LTV for every $20 that they spend, it is optimal to spend as much money as possible. However, the amount of money that they can spend is directly influenced by the payback period.

Capital Efficiency

The payback period, or capital efficiency, of a business is based on the amount of time it takes to get back $1.00 of capital for every $1.00 of spend.

When the unit economics and payback period are healthy, the business can spend $20 to acquire a customer, generate $40 in LTV, and recycle the profit back into growth. This creates a perpetual feedback loop that allows the business to grow profitably over time without any external capital.

Businesses that have figured out the profitable-growth feedback loop are able to raise capital and grow faster.

Profitable Growth

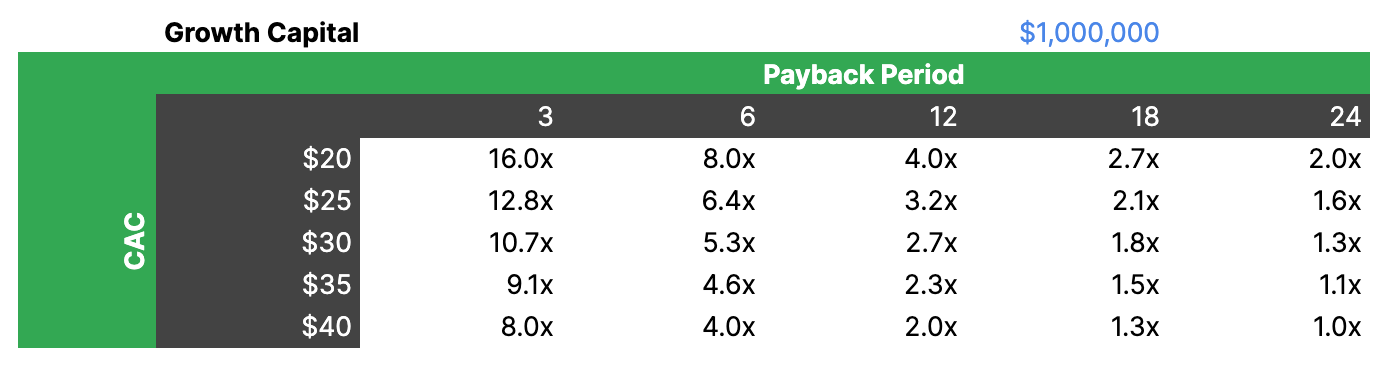

Growth capital is the amount of money that a startup allocates to acquiring new customers. The amount of capital needed is directly related to the customer-acquisition costs (CAC) and the payback period.

Illustratively, a startup with a 3-month payback period can grow 8X faster on a monthly basis than a startup that has a 24-month payback period with the same amount of growth capital.

In a capitally-inefficient business, the payback period can be too long and growth becomes dependent on being able to raise external capital. An example of this could be a business that spends $1,000 to acquire a customer today and generates $5,000 uniformly over the next 10 years.

Growth-At-All Costs

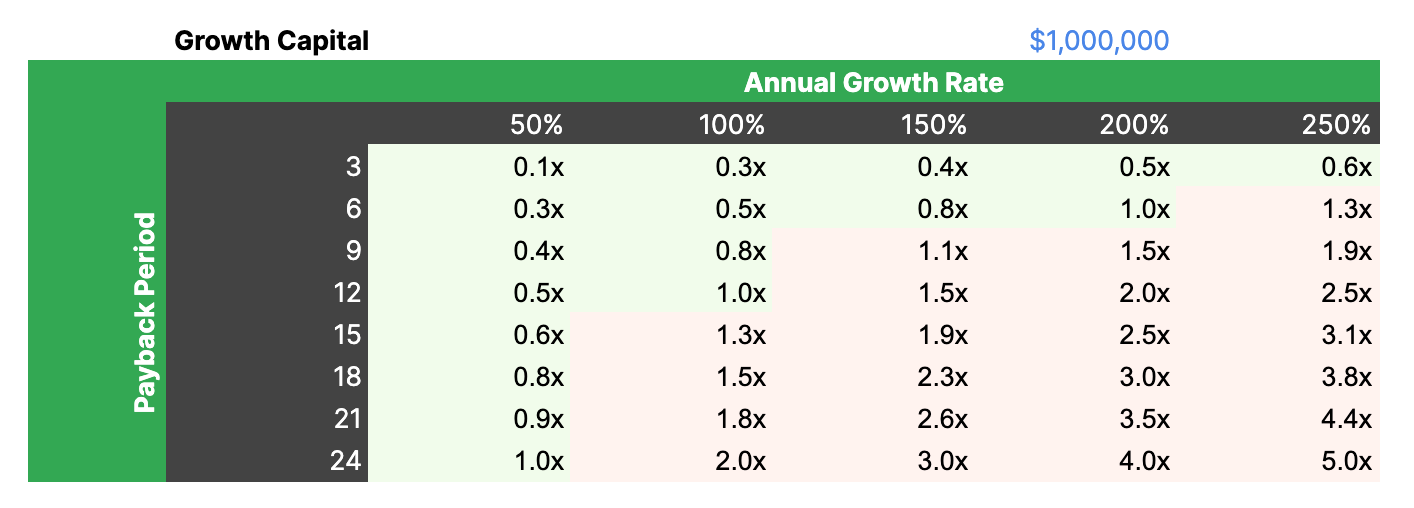

In the current market climate, the nuance between growth rate and payback period becomes more important to understand. Fast-growing startups consume cash, and the faster they grow, the more cash they consume. This problem only gets larger with scale.

If a startup has an extended payback period (e.g. 24 months), it can consume more capital than the market is willing to support. For example, a startup that is growing 3X YoY with a 24-month payback will require 16X more growth capital (i.e. 4x in the first year, and 4x in the second year) to continue its trajectory over the next two years 😬.

When calculating payback period, it is important to include all variable costs, such as direct variable costs (e.g. COGs) and indirect variable costs (e.g. centralized operating costs). If indirect variable costs are not included, the payback period and capital requirements could be much higher than expected.

Irrational Exuberance

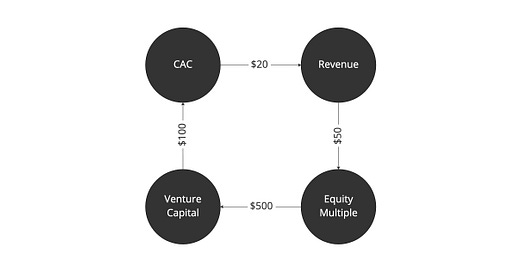

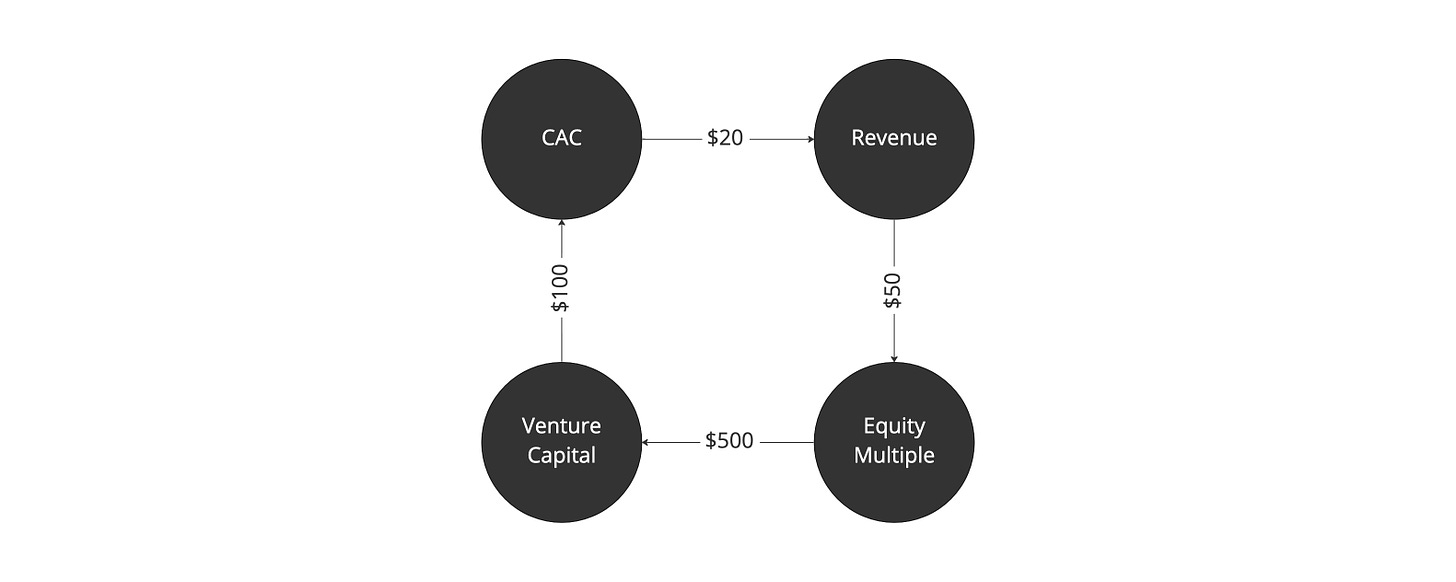

In the era of low interest rates, startups and public valuations started to get disconnected from business fundamentals and profitability. In a sense, startups could spend $20 to generate $50 in revenue, generating $50 in revenue created $500 in equity value, and they could sell 20% of their equity for $100.

Since this is what the market rewarded, startups shifted more and more of their ad spend to unprofitable campaigns because it increased top line revenue. While this view is myopic across market cycles, it was the most optimal strategy for short-term value creation for shareholders.

This forced other disciplined startups to loosen their ad spend to be competitive in the venture-market industry and created an era of capital-inefficient businesses. With time, this will re-adjust back to historical norms and the process will be painful.

Closing

At the end of the day, capital efficiency and profitability are the most important metrics for running a successful technology business. If a startup can generate positive unit economics with a short payback period, it can generate perpetual growth. If it cannot, it will have to rely on external capital to grow and endure the risk of running out of cash.

Revenue is easy, profit is harder.

Great article Ryan! We will likely see a lot of startups struggle in the coming year due to inverted cash flows.

Of course, there are some businesses (like SpaceX) that just take a ton of money to get going. If you're building spaceships, tough to get around that! But many software companies, particularly in these days of AI-boosted software development, don't need that kind of up front capital.